Post-election policy debates concerning the future of the Affordable Care Act focus heavily on the 20 million people who gained health insurance coverage under the law. But the future of less-visible components of the law – especially its population health provisions – may be equally important to the nation’s long-run health and economic wellbeing. Which provisions should be scaled up or down as U.S. policymakers revisit health reform over the next four years?

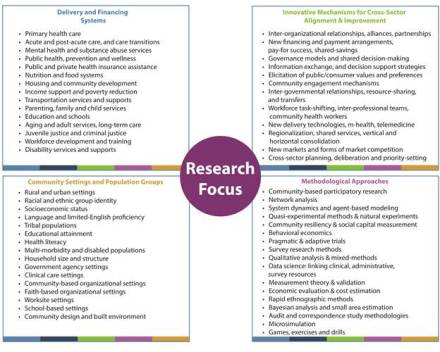

The ACA stimulated a surge of new interest in the science and practice of improving population health. The aim of this work is to improve health status for large groups of people and entire communities, rather than doing so one patient at a time through an expensive and fragmented medical care system. This work includes upstream strategies for keeping people healthy in order to reduce the flow of patients into the medical system with preventable health conditions. The ACA established population health improvement as a central component of the Triple Aim strategy on which many of the law’s payment and delivery system reforms are based. Since then, hospitals, health systems, insurers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, information technology companies and large employers have created new organizational units devoted to population health. And public health professionals and preventive medicine specialists also claim large swaths of territory in the population health frontier.

Despite this enthusiasm, population health strategies remain controversial due to their heterogeneity and lingering uncertainties about their effectiveness. Over the past 6 years, a wide array of population health initiatives have been developed and tested, including those supported by the ACA’s Prevention and Public Health Fund and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. What is lacking in the emerging field of population health is a coherent description of the essential ingredients, backed up by sound research. What capabilities does every community need in order to succeed in improving health status for the population at large? A 2012 National Academy of Medicine study called for additional research to define this set of foundational capabilities and to quantify the resources required to establish these capabilities in every community.

This month the journal Health Affairs published results from one of our new studies that sheds light on this question by combining information from a long-running national survey of communities, “hard” data on health outcomes, and strong econometric methods. Specifically, our study examines whether certain combinations of population health activities lead to improved health outcomes when implemented over time by community organizations.

Measuring Population Health Activities

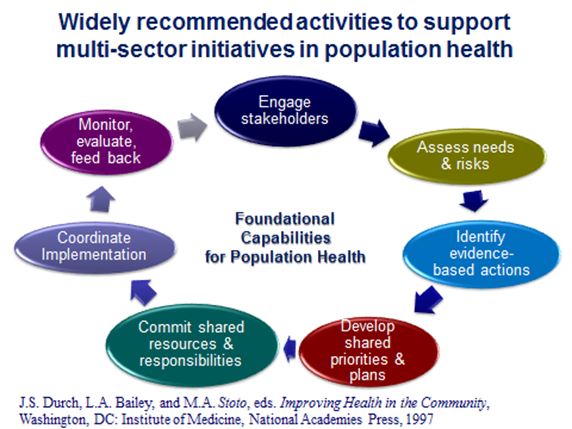

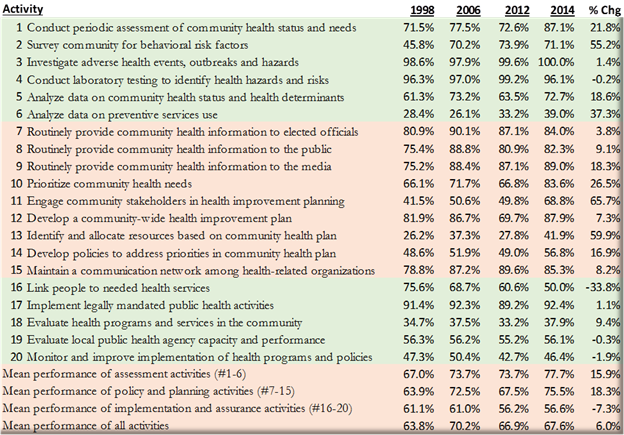

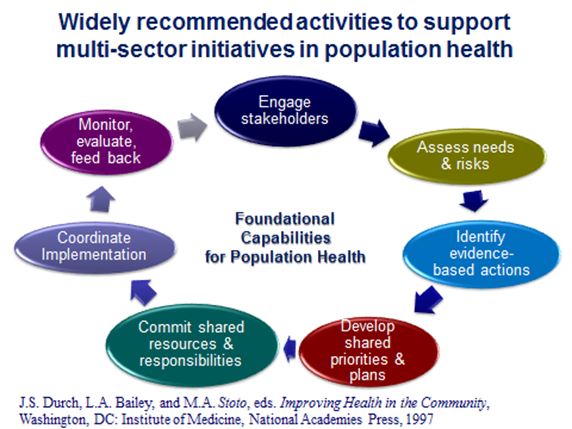

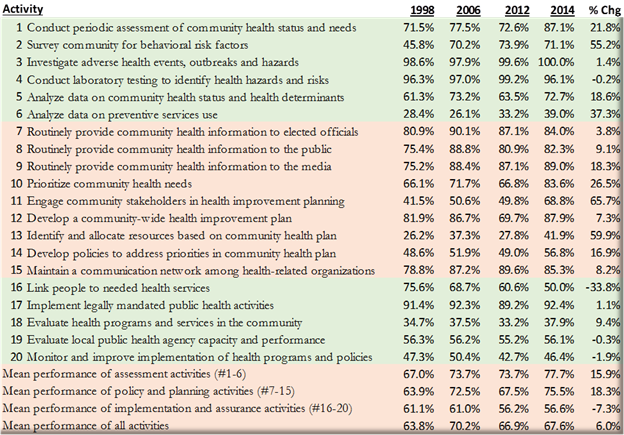

We followed a national cohort of more than 300 communities over a 16 year time period to examine the extent to which community organizations work together in implementing a set of activities designed to improve health status in the community at large. The population health activities measured in this study are based on practices long recommended by the National Academy of Medicine and other scientific and professional advisory groups. These activities include conducting regular assessments of health status and needs in the local area, developing shared priorities and plans for health improvement, educating community residents and leaders about health priorities, investing resources in shared health priorities, and evaluating the results of these investments. These activities are reflected in many current national guidelines and model practices for health improvement, including CDC’s Community Health Improvement Navigator program, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Foundational Public Health Services framework, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Public Health 3.0 framework.

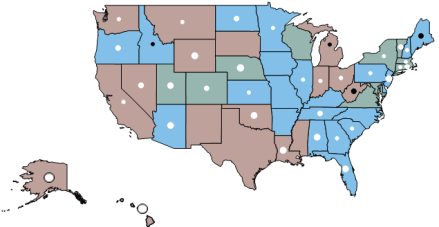

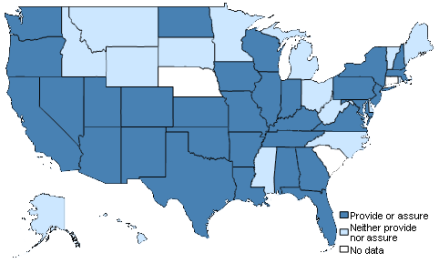

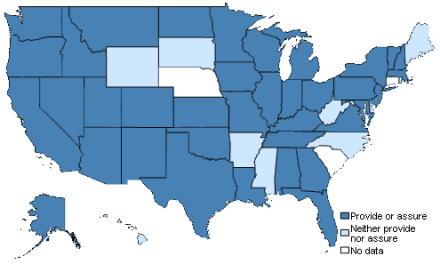

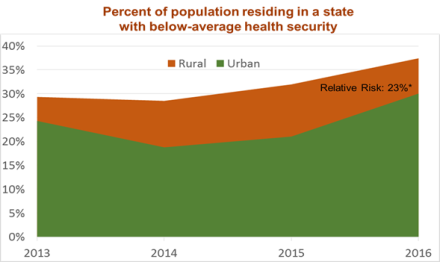

Prevalence of Population Health Activities in U.S. Communities

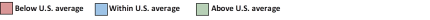

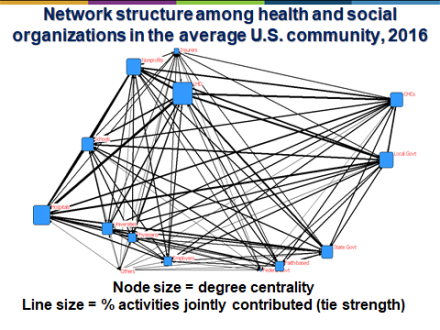

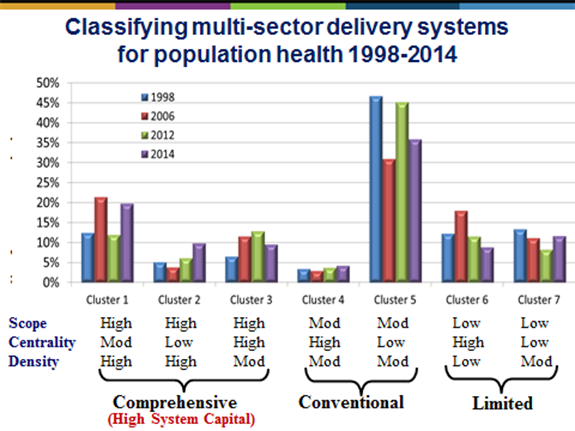

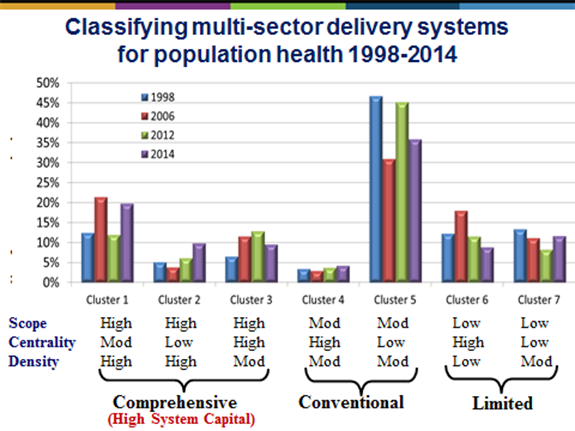

We used cluster analysis methods to classify communities into comparison groups based on the spectrum of population health activities implemented in each community and the constellation of organizations engaged in implementing these activities. Communities that implement a broad spectrum of population health activities through dense networks of collaborating organizations are classified as comprehensive delivery systems for population health activities, while the remaining communities were classified either as conventional or limited delivery systems based on their spectrum of activities and collaborative networks.

Estimating Outcomes Attributable to Population Health Activities

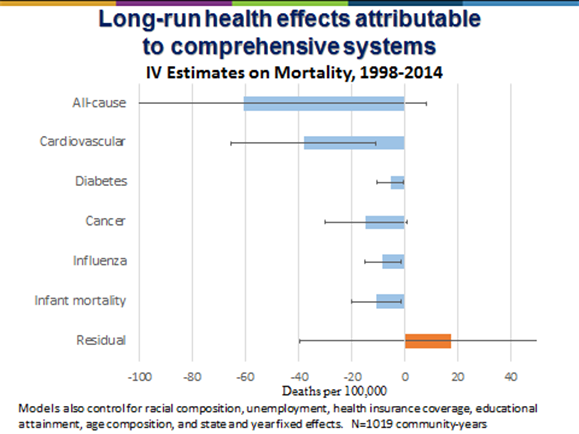

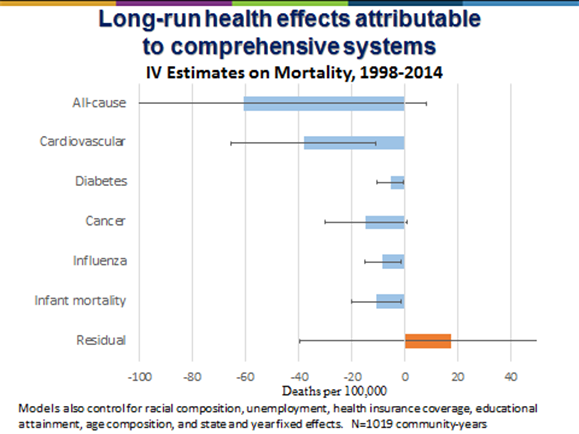

We linked survey data on population health activities in more than 300 communities with county-level health outcome measures indicating deaths from potentially preventable conditions during the period 1998 to 2014. We also linked these data with a rich set of measures reflecting community demographic, socioeconomic, and health resource characteristics. Collectively, these data allow us to track how the spectrum of population health activities in each community changes over time, and how these changes relate to health outcomes. Using the method of instrumental variables analysis, we generate causal estimates of how changes in population health activities impact community mortality rates after adjusting for other determinants of health in the communities.

By carefully analyzing data spanning 16 years, the results showed that deaths from preventable causes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, influenza and infant mortality declined significantly among communities that implemented a broad spectrum of population health activities through dense networks of collaborating organizations. Preventable deaths were more than 20 percent lower in the communities with the strongest networks supporting population health activities, compared to communities with less comprehensive networks. These differences in mortality persisted after controlling for a wide range of demographic, socioeconomic, and health resource characteristics in the communities, including using causal estimation methods that control for unmeasured community differences.

Drawing Conclusions about What Is Foundational

These results give us the clearest picture yet of the health benefits that may accrue to communities when they build broad, multi-sector networks to improve population health. Achieving better outcomes in this study was not simply a matter of implementing widely-recommended activities involving assessment, planning, priority-setting, resource deployment, and evaluation. Communities needed to implement a broad spectrum of activities and engage a full range of partners in these activities in order to reduce mortality. The results suggest that strong collaborative networks help communities arrive at the best decisions about how to invest limited resources in high-impact health solutions.

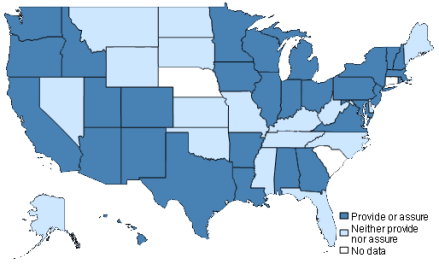

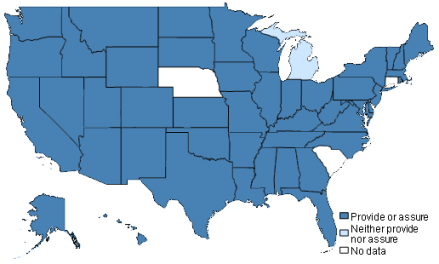

The population health activities examined in the study include those now incentivized through the federal Affordable Care Act and related health reform initiatives. Tax-exempt hospitals are required to conduct community health needs assessments in their local service areas, develop community health improvement plans, and report annually on their expenditures related to community benefit activities. And state and local public health agencies are required to undertake similar activities in order to meet voluntary national accreditation standards. The communities that achieved significant reductions in mortality in this study, however, progressed beyond health assessment and planning activities to include shared investment of resources along with monitoring and evaluation activities.

Perhaps most importantly, the communities that achieved sizable reductions in mortality appeared to do so by engaging broad networks of organizations in implementing population health activities rather than relying on independent and uncoordinated efforts. The network effects appear to be major drivers of these results, which are consistent with a growing body of research indicating that community networks can function as force multipliers.

Taken together, these results suggest that foundational ingredients of population health activities include mechanisms that:

· Engage dense networks of stakeholders across the medical, health and social sectors

· Support recurring cycles of community health assessment

· Develop shared priorities and plans for health improvement

· Educate community residents and leaders about health priorities

· Invest resources in shared health priorities

· Monitor and evaluate the results of investments

We recommend that these key ingredients receive careful consideration in the post-election “keep or kill” policy debates about the future of ACA’s population health components.

What Can We Say about Cost and Value?

A complete understanding of the value of population health activities to society requires estimates of both benefits and costs. Estimating the resources required to implement population health activities is beyond the scope of our Health Affairs study, which focused only on estimates of health impact. Nevertheless, post-election “keep or kill” debates about ACA and population health are likely to focus heavily on costs as well as benefits.

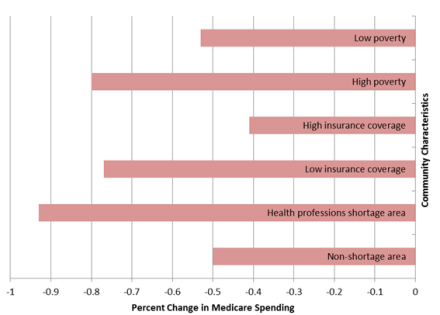

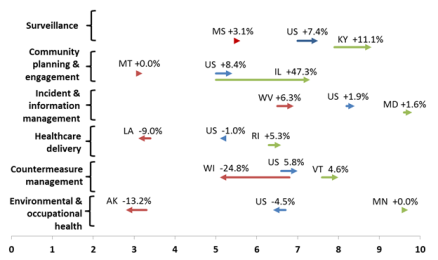

We recently conducted a related study to generate first-generation estimates of the costs required to implement Foundational Public Health Services as recommended by the National Academy of Medicine and as defined by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supported expert panel process. The services defined and measured in this new costing study do not perfectly match the population health activities measured in our Health Affairs study, but the two sets of measures are closely aligned conceptually. As a result, it is instructive to compare the health impact estimates from our Health Affairs study with the cost estimates from the costing study.

Results from the costing study indicate that full implementation of foundational population health activities in every U.S. community would require $26.3 billion per year in 2016 dollars, a total that is about 70% larger than the estimated $15.4 billion currently spent on these activities in 2015-16. Combining these cost estimates with the mortality reduction estimates produced in the Health Affairs study (and making some conservative assumptions about how mortality reductions translate to life expectancy gains), we estimate that the cost per life-year gained through investments in population health activities is on the order of $7,200 – a number that implies foundational population health activities are potentially a very wise investment.

Of course these estimates of value are very crude back-of-the-envelope calculations, requiring further analysis and refinement. Our research team along with many others are continuing to study these issues with the hope of informing ongoing decisions in health policy and health systems. Our research is part of the new Systems for Action research program created by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of its national action framework for building a Culture of Health. Based at the University of Kentucky, Systems for Action supports research that evaluates mechanisms for aligning medical care, public health, and social services in ways that improve health and wellbeing.

I invite you to stay up to date on the research progress by following this blog, the Systems for Action website, my research archive, and my twitter feed.