Parts of the U.S. economy are finally showing some signs of real rebound, but what about the nation’s public health enterprise? A new paper in the American Journal of Public Health offers a broad view of changes in public health delivery before and after the Great Recession of 2008. The results show that in communities hardest hit by the recession, public health protections remain far below their pre-recession levels. Consequently, disparities between the strongest and weakest public health delivery systems have widened considerably since the recession.

The National Longitudinal Survey of Public Health Systems (NLSPHS) tracks changes in the organization and delivery of core public health activities in a nationally representative cohort of metropolitan communities across the U.S. Our research center has conducted this survey periodically since 1998, and two recent waves of the survey – in 2006 and 2012 – span the most recent period of economic recession and the initial phases of recovery.

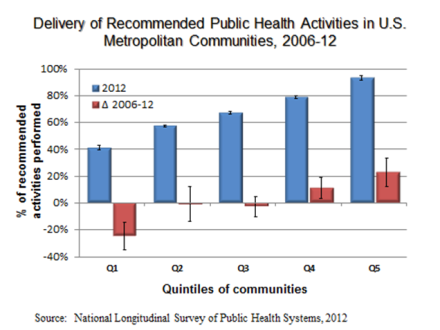

We reported previously that between 2006 and 2012, the average U.S. community experienced a 5% reduction in the proportion of recommended public health activities that were actually implemented in the community. However, this average decrement in public health protections masks considerable heterogeneity across the U.S. The bottom 20% of communities experienced a whopping 25% reduction in the delivery of core public health activities over this timeframe, while the top 20% of communities gained additional activities despite the economic contraction (see figure). The net result was a widening of the gap between the “haves” and the “have nots” in terms of community-wide public health protections.

Multivariate estimates confirmed what any informed model of public health production predicts: local public health delivery fell most sharply among communities that experienced the largest reductions in public health agency spending and household income and the largest increases in unemployment. Perhaps most surprising, however, were the magnitudes:

“a 10% reduction in public health agency spending per capita was associated…with a 31 percentage-point reduction in the availability of public health activities, a 36 percentage-point reduction in the intensive margin of activities contributed by local public health agencies, a 6 percentage-point reduction in the extensive margin of activities contributed by other organizations, and a 29 percentage-point reduction in the perceived effectiveness of public health activities.”

The recession also triggered some key changes in the production of public health activities, as both government and private-sector organizations adjusted their contributions to these activities. Overall, hospitals, health insurers, and community health centers showed more modest reductions in their contributions to public health activities than did government agencies – likely reflecting differences in the resiliency of the revenue sources that these different organizations tap. The net result is that many local public health delivery systems today are much more reliant on contributions from the medical care sector than they were before the recession. This growing co-dependency between public health and medical care delivery may prove to be beneficial over time as initiatives like the CMS State Innovation Models attempt to better align the prevention and treatment ends of health care delivery and financing systems in order to realize population-wide improvements in health status.

The recommended public health activities measured in the NLSPHS reflect a set of 20 programs, policies and administrative practices that national expert panels have consistently recommended to be performed in every U.S. community in order to prevent disease and injury and promote health. This recommended set includes activities to monitor community health status, investigate and control disease outbreaks, educate the public about health risks and prevention strategies, prepare for and respond to natural disasters and other large-scale health emergencies, and enforce health-related laws and regulations such as those concerning tobacco exposure, food and water safety, and air quality. These 20 activities are based on the Institute of Medicine’s Core Public Health Functions definitions and reflect high-value practices recommended by a series of expert panels convened by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These activities are also closely aligned with the federal government’s Essential Public Health Services Framework and a more recently developed set of Foundational Public Health Capabilities called for by the Institute of Medicine in its 2012 consensus report on public health financing.

These results beg important questions about how public health delivery systems are evolving now as the recovery lurches forward and as key ACA coverage expansion provisions take hold. Fortunately, we are wrapping up a 5th wave of NLSPHS data collection this month, which for the first time will include a large expanded sample of small and rural communities across the U.S. Stay tuned for preliminary findings to be released at next month’s Keeneland Conference on Public Health Services & Systems Research.

The paper described in today’s post is part of an entire supplement issue of the American Journal of Public Health devoted to advances in public health services & systems research, slated for official release in April (thanks to support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and CDC). As the guest editor of this issue, I will be posting highlights from some of my favorite articles on this blog over the next few weeks leading up to the official release. All of these papers are available early online so I encourage readers of this blog to take a peak and post comments here about your observations.

I invite you to comment on this blog, tweet at me, nudge me on linkedin, and follow my research archive.